|

Reviews

The Washington Post

Galleries, p E9

Sunday, December 8, 2013

by Mark Jenkins

Nancy Wolf appreciates the clean lines and simple forms of Bauhaus-style architecture. But she’s an artist,

not an architect, so she has to ask: Where do people and tradition feature in the International Style’s attempt to

cleanse cities of their historic character?

It’s a question she has been asking for 40 years as “Nancy Wolf: Landscapes of Unease” demonstrates. The

Marsha Mateyka Gallery retrospective begins with 1972’s “The Underpass”, in which gaps in an immaculate grid

reveal unruly pedestrians below. It ends with 2013’s “High Line/Low Line”, in which centuries of

architectural features promenade on Manhattan’s railway-turned-park, past blank high-rise facades.

During the period these detailed drawings were made, Wolf lived mostly in New York, but also in

Washington’s “new Southwest” and Nigeria, and she traveled extensively in Asia. All those

places are reflected in her work, as are baroque Italy and Le Corbusier’s severe plans for

France. “Perfect Order” shows a city divided into zones so rigidly that it’s even more absurd

than the architect’s scheme to replace Paris with a series of identical tower blocks.

Often, Wolf seems bemused or playful, as when she contrasts traditional Nigerian geometric motifs

with modernist and industrial structures. But sometimes she’s regretful or even

angry: “The Past Has No Future” shows a leaning New York skyscraper that’s supported by the

facades of the many 19th century beauties demolished to make room for it.

Among the most trenchant drawings are those that depict a rapidly changing China. Traditional

buildings and layouts, as well as the landscapes of venerable Chinese painting, are displaced by

culturally unrooted edifices such as Rem Koolhaas’s CCTV headquarters in Beijing.

“Reconstruction/Deconstruction” places the CCTV oddity amid a vast archaeological dig, like the

one that yielded the Terra Cotta Warriors.

Wolf works mostly in pencil, rendering both modernist lines and classical curves with extraordinary

precision. But occasionally she incorporates color, using gouache, acrylic and colored pencil. The

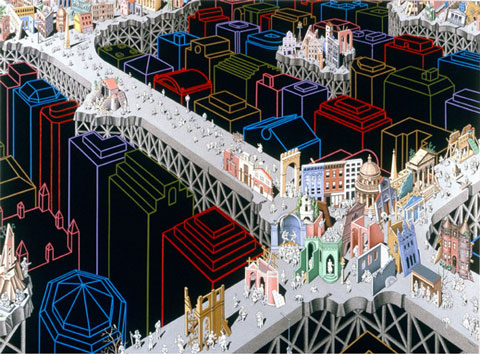

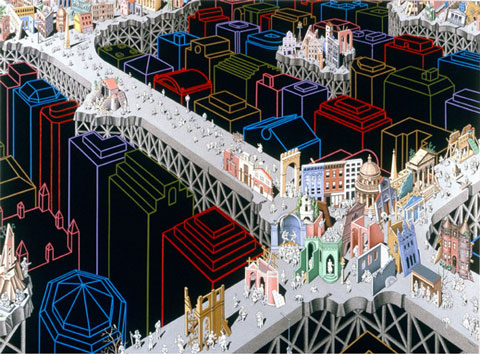

astonishingly complex “Pilgrimage” contrasts old and new, specific and general: Pilgrims wander

elevated causeways above skyscrapers outlined in bright hues against black, on a quest toward

architectural variety rather that monomaniacal modernism.

“LANDSCAPES OF UNEASE”: Nancy Wolf’s “Pilgrimage” (1993, acrylic on canvas)

contrasts old and new, as well as specific and general.

Nancy Wolf: Landscapes of Unease

On view through December 21 at Marsha Mateyka Gallery, 2012 R Street, NW,

202 328-0088, www.marshamateykagallery.com

|

|

|

ARTnews

Summer 2008, Volume 107, Number 7

"Nancy Wolf", Marsha Mateyka, Washington, DC, by Rex Weil

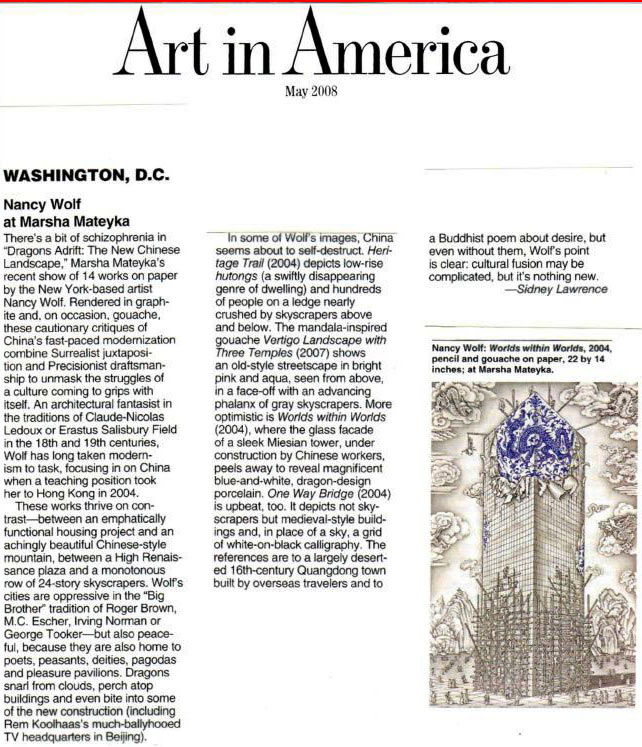

Art in America

May 2008, Page 200

Nancy Wolf at Marsha Mateyka, by Sidney Lawrence

THE WASHINGTON POST

Style , 12/12/02 p. C5

Arts, "Galleries" by Jessica Dawson

"A Top-Drawer Show, Nancy Wolf's Pencil Evokes the Baroque at Marsha Mateyka"

Is drawing the new painting? Laura Hoptman, organizer of the much praised New York exhibition "Drawing Now", up until Jan. 6 at the Museum of Modern Art's outpost in Queens, seems to thinks so. Simple sketches and preparatory studies need not apply. Hoptman's picks boast as much time, effort and finish as any work on canvas. Intricate ends unto themselves, these pictures have a nearly 19th-century zest for description and narrative.

I couldn't help but think of Hoptman's show while checking out Nancy Wolf's pencil drawings at Marsha Mateyka Gallery here in Washington. Wolf's works, as packed with information as a Bosch painting and as precise as old anatomical illustrations, are of a piece with works in that MoMA show. They'd fare well in Hoptman's "visionary architecture" section, alongside Paul Noble's Tower of Babel-style visions in graphite.

Wolf's pictures are both barometers of the latest architectural developments and cautionary tales about the urban landscape. She juxtaposes versions of contemporary and historical buildings to create desolate uber-cities populated by hordes of tiny figures recognizable from Renaissance painting, commedia dell'arte and Voque.

I suspect Wolf's reliance on postmodern pastiche kept her out of a show like MoMA's, with its emphasis on innovative style. Nevertheless, her mix of familiar faces and forms forces the eye to roam again and again across her pictures, picking up new details every time. Culture vultures, especially aficionados who have tracked New York's recent architectural developments, can scan Wolf's drawings and find quotations of the latest in design.

From her studio in SoHo, Wolf has kept an eye on neighborhood transformation. She isn't pleased. Irked by the tyranny of the fancy-pants set, who have turned former warehouses into Prada outlets and multimillion-dollar condos, she registers a complaint in "Loft Follies": A massive rehabbed loft building sprouts a ceremonial staircase lifted from an Asian palace. Eighteenth-century ladies and Chinese dignitaries populate the scene; only the well-top-do, it seems, can live here. To underscore her point, Wolf transplanted Christian de Portzamparc's dazzling Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton tower from its spot on 57th' Street to her downtown scene. The luxury conglomerate's faceted skyscraper stands implicated in the theft of urban life from regular Joes.

The witty way that Wolf taps centuries-old architectural forms to make her arguments, and the exuberance of her renderings of the posh addresses she reviles, help Wolf avoid mere hand-wringing. In fact, I'm not altogether sure she isn't a bit excited by the architectural and economic clashes she chronicles. She hasn't alienated the Prada shoppers, she's co-opted them.

It's true that New Yorkers of late have been witnessing a rollout of tour de force design from conglomerates hoping to build their own Emerald Cities. But the fact remains that the rich and powerful have been transforming cities for millennia. Baroque Rome with its powerful popes who converted avenues and piazzas into grand stage sets, was the same kind of place.

Wolf makes the same connection between baroque theatrics and modern-day built environments, lifting motifs from 17th-century French engraver Jacques Callot and inserting them next to titanium tornadoes by modern-day-baroque architect Frank Gehry. In her vision, they're two of a kind.

Gehry's undulating forms hang in the air like dark clouds over a downtown still shaken by the World Trade Center collapse. The twin towers have appeared frequently in Wolf's drawings over the past two decades, and their cataclysmic demise, too, has found a place in "Remains of the Day". She's enlisted a Callot-style dragon from the Frenchman's spooky chronicle of sin, "The Temptation of Saint Anthony", to oversee a scene of mayhem populated by skeletons, rescue workers and the Grim Reaper. While something of a paradox, invoking baroque Sturm und Drang files the recent tragedy next to centuries of disasters and cautionary tales, making Wolf's piece one of the least hysterical reactions to Sept. 11 I've seen so far. Hoptman, who is curator of contemporary art at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, may have overlooked Wolf for her MoMA show, but the artist's vision places her squarely in the Now of both draftsmanship and culture.

|