Reviews

Houston Chronicle

Arts & Theater, July 1, 2016

“Artist Jae Ko: This is how she rolls”

by Molly Glentzer

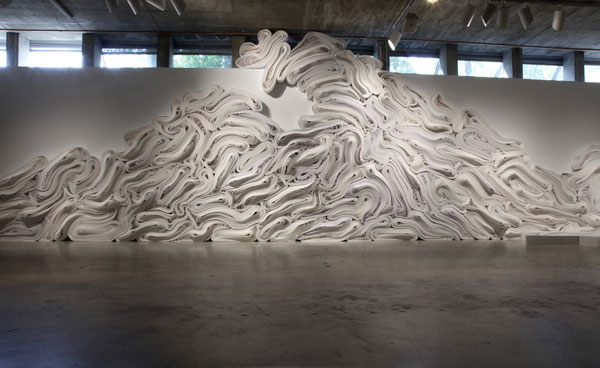

Just as summer temperatures begin to feel unbearable, glaciers appear to have slid down

the walls in the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston’s Zilkha Gallery.

They could be melting or rising.

“Flow,” a poetic, site-specific installation by artist Jae Ko, is composed from about 2 tons of recycled, bleached Kraft paper in large rolls that the artist has transformed, through a laborious process, into a malleable material that she fastens to walls and spills on the floor.

The way the rolls flow around each other is reminiscent of dense embroidery, full of turbulent “stitches.”

Ko also thinks of her work as a kind of three-dimensional drawing. She often pulls the center of a roll outward or shoves it inward, creating a ripple effect of countless “lines” that also suggest layers of topography.

“When the light hits it…every time you move, the lines follow you. I always enjoy watching this,” she said.

Ko, a native of Korea who lives near Washington, D.C., has always been fascinated by America’s vast landscapes. She and her husband, sculptor James Sanborn (whose monumental installation “A Comma A” stands outside the University of Houston’s library) have sought out grand vistas since 1998.

They drove from Washington state through Alaska to the Arctic Circle, as far as they could go, in 2002 and also explored Canada’s northeast, looking for icebergs.

“Years of traveling--all these geological shapes, organic shapes of ideas--are put into this,” Ko said.

She doesn’t mind if viewers see something completely different.

“They have a right to,” she said.

The first work of Ko’s to be shown at the museum, “Flow” belongs to a series she calls “Force of Nature.”

She spent 10 days reconfiguring it in Houston, but the elements are recycled from a larger installation, “Shiro” that evoked snowy scenery earlier this year at a place with much higher ceilings, the Grounds for Sculpture in Hamilton, N.J.

The installation gets added depth from the slight variations of color in the paper. That wasn’t planned, Ko said.

She had ordered one color of paper and was angry when it arrived on four pallets--each a different color--at the New Jersey site, where she and 11 assistants spent five weeks unrolling it, re-rolling it more loosely without the spools and installing it. They didn’t have time to wait for another order, so Ko went with the, um, flow.

“I thought, maybe it could be interesting. Just work with it instead of getting (ticked off),” she said. “Accidents are always good.”

Ko studied graphic and commercial design in Japan before moving to the U.S. to earn her MFA. Inspired early on by calligraphy and traditional Asian hairstyles, she has experimented with all kinds of paper as a sculptural medium.

She buried Kraft paper in beach sand for one of her early projects but happened upon her signature--the roll-based sculptures--after she discovered boxes of machine paper at an office-supply store in 1996.

“I didn’t know what I was looking for. I saw these tiny rolls being sold in boxes, cheap. So I grabbed a box, “she said.

She tried soaking the rolls in water, cutting them, burning them; and as she began to master the material, she also began to dye it with pigment and manipulate it with glue to make wall reliefs and spiraling, free-standing sculptures.

Ko’s work for site-specific installations started out with rolls of Kraft paper that were factory-size, 48 inches wide. She’s worked her way down to a 5-inch width now--so she can manipulate the paper by hand and doesn’t need a crane to hang it.

The rolls of “Flow” are made from 90-pound stock, a bit thicker that a book jacket.

With Ko’s touches, the museum’s dark and cave like basement feels like a different place. She wanted daylight--and lo and behold, the space has room-length rows of high windows that have long been covered.

“I wanted to make it as bright as possible, to have a cold, snowy, artic feeling during this steamy Houston weather,” she said. “Lowering the temperature might help, too.”

They could be melting or rising.

“Flow,” a poetic, site-specific installation by artist Jae Ko, is composed from about 2 tons of recycled, bleached Kraft paper in large rolls that the artist has transformed, through a laborious process, into a malleable material that she fastens to walls and spills on the floor.

The way the rolls flow around each other is reminiscent of dense embroidery, full of turbulent “stitches.”

Ko also thinks of her work as a kind of three-dimensional drawing. She often pulls the center of a roll outward or shoves it inward, creating a ripple effect of countless “lines” that also suggest layers of topography.

“When the light hits it…every time you move, the lines follow you. I always enjoy watching this,” she said.

Ko, a native of Korea who lives near Washington, D.C., has always been fascinated by America’s vast landscapes. She and her husband, sculptor James Sanborn (whose monumental installation “A Comma A” stands outside the University of Houston’s library) have sought out grand vistas since 1998.

They drove from Washington state through Alaska to the Arctic Circle, as far as they could go, in 2002 and also explored Canada’s northeast, looking for icebergs.

“Years of traveling--all these geological shapes, organic shapes of ideas--are put into this,” Ko said.

She doesn’t mind if viewers see something completely different.

“They have a right to,” she said.

The first work of Ko’s to be shown at the museum, “Flow” belongs to a series she calls “Force of Nature.”

She spent 10 days reconfiguring it in Houston, but the elements are recycled from a larger installation, “Shiro” that evoked snowy scenery earlier this year at a place with much higher ceilings, the Grounds for Sculpture in Hamilton, N.J.

The installation gets added depth from the slight variations of color in the paper. That wasn’t planned, Ko said.

She had ordered one color of paper and was angry when it arrived on four pallets--each a different color--at the New Jersey site, where she and 11 assistants spent five weeks unrolling it, re-rolling it more loosely without the spools and installing it. They didn’t have time to wait for another order, so Ko went with the, um, flow.

“I thought, maybe it could be interesting. Just work with it instead of getting (ticked off),” she said. “Accidents are always good.”

Ko studied graphic and commercial design in Japan before moving to the U.S. to earn her MFA. Inspired early on by calligraphy and traditional Asian hairstyles, she has experimented with all kinds of paper as a sculptural medium.

She buried Kraft paper in beach sand for one of her early projects but happened upon her signature--the roll-based sculptures--after she discovered boxes of machine paper at an office-supply store in 1996.

“I didn’t know what I was looking for. I saw these tiny rolls being sold in boxes, cheap. So I grabbed a box, “she said.

She tried soaking the rolls in water, cutting them, burning them; and as she began to master the material, she also began to dye it with pigment and manipulate it with glue to make wall reliefs and spiraling, free-standing sculptures.

Ko’s work for site-specific installations started out with rolls of Kraft paper that were factory-size, 48 inches wide. She’s worked her way down to a 5-inch width now--so she can manipulate the paper by hand and doesn’t need a crane to hang it.

The rolls of “Flow” are made from 90-pound stock, a bit thicker that a book jacket.

With Ko’s touches, the museum’s dark and cave like basement feels like a different place. She wanted daylight--and lo and behold, the space has room-length rows of high windows that have long been covered.

“I wanted to make it as bright as possible, to have a cold, snowy, artic feeling during this steamy Houston weather,” she said. “Lowering the temperature might help, too.”

The Washington Post

May 11, 2014, page 4, section E

"In the Galleries"

by Mark Jenkins

Jae Ko

Glue, paper and black ink were the only ingredients when Jae Ko began making her distinctively coiled sculptures from rolls of adding-machine paper. The Korean-born local artist was doing a sort of 3-D calligraphy, working with the same materials used in Asian brush painting. So it was natural for her to expand her palette slightly, adding red ink to the glue that both colors and binds the paper, or brushing the black sculptures with graphite powder.

Jae Ko’s “Recent Sculpture and Drawing” at Marsha Mateyka Gallery adds a new color, but it’s not really new. Two of the elegant vertical wall sculptures are white, which is just an amplified version of the paper’s original color. More surprising are the works dubbed drawings, which were executed with thin vinyl cord on adhesive paper. Painstakingly fashioned, these arrangements in white, black, red and--another color!--turquoise resemble furrows, fingerprints and phonograph records.

The drawings aren’t as formidable as the sculptures, whose sleekly twisting forms suggest painted wood or metal. But their many patterns, more abundant than those in the coiled paper, carry the eye in unexpected directions. The spiraling vinyl strips suggest the rolls of paper Jae Ko has used for two decades, while demonstrating her carefully limited gambits can be extended without limit.

The Washington Post Express

On the Spot: Jae Ko

Posted on April 04, 2012

by Mark Jenkins

Korea-born, Washington-based artist Jae Ko is having her seventh solo exhibition at Marsha Mateyka Gallery, near Dupont Circle. Ko works with ink and paper but makes sculpture rather than drawings: She twists rolls of adding-machine tape into coiling forms, held in place by glue and ink.

After years of using only black ink, why did you add red for this show?

Black goes back to calligraphic writing, part of my Asian background. But I was starting to miss using color. Red is difficult to use; I had to find the right kind of red. In East Asia, red is the color of happiness.

Why do you add graphite to the ink?

Glue mixed with pigment often dries to a shiny, rubbery color. Graphite reduces this quality. I rub the graphite powder lightly on the work to enhance the details and bring out the layers of the paper.

Do you think you’ll ever exhaust this technique?

I once took a roll of paper to the ocean, buried it in the sand and recovered it several hours later to discover how the paper changed. I don’t feel I will ever get exhausted because there are so many other ways I still have to experiment.

What interests you about these forms?

The shape right at the point the work’s almost collapsing--another push or pull might ruin the work. I am inspired by pushing the limits of shaping paper into these forms.

The Washington Post, Going Out Guide

On Exhibit, page 18

Friday, March 30, 2012

"Exhibit adds up to a thrill: Jae Ko's sculpture leaps to sinuous,

sensuous life at Marsha Mateyka Gallery"

by Michael O'Sullivan

There's an inherent tension in Jae Ko's sculpture, on view at the Marsha Mateyka Gallery in a handsome installation of nine new pieces, including three unusually large works.

The most obvious tension is physical. Made from fat, ropelike coils of the artist's signature adding-machine tape that she manipulates and twists like taffy—see "The Story Behind the Work"—Ko's art has the springy energy of a snake about to strike. It's pure potential, like a muscle that has contracted in anticipation of throwing a punch.

The impact is not just visual; it's visceral.

There's another tension, too. Ko's latest works straddle a line between the biomorphic and the machine-made. From some angles, they don't look made so much as grown.

Inspired by the gnarled trunks of bristlecone pines—which the artist encountered on a trip

to California and which are said to be the oldest organisms on the planet, living thousands

of years—they seem shaped by powerful, unseen forces. But they also resemble giant,

misshapen augers, rejects from some Bunyanesque tool-and-die plant.

Inspired by the gnarled trunks of bristlecone pines—which the artist encountered on a trip

to California and which are said to be the oldest organisms on the planet, living thousands

of years—they seem shaped by powerful, unseen forces. But they also resemble giant,

misshapen augers, rejects from some Bunyanesque tool-and-die plant.One serpentine floor piece is 13 feet long. Two wall pieces---spiraling in thick ringlets—stretch more than six feet.

For this show, Ko has restricted her palette. Roughly half of the works are black which

underscores their cold, industrial feel. The others are covered in a bright, lipstick-red pigment,

bringing them to sinuous, sensuous life. The tension between opposites lends visual interest to

Ko's work, which has for several years been among the area's most formally elegant sculpture.

For this show, Ko has restricted her palette. Roughly half of the works are black which

underscores their cold, industrial feel. The others are covered in a bright, lipstick-red pigment,

bringing them to sinuous, sensuous life. The tension between opposites lends visual interest to

Ko's work, which has for several years been among the area's most formally elegant sculpture.Once known for flat, wall-mounted pieces that were all about the quiet contemplation of surface, a la Anish Kapoor, the artist's latest sculptures are a leap forward. They seem to hold an implicit threat.

That makes them ever so slightly dangerous, but in a way that thrills more than chills.

The Story Behind the Work

Jae Ko's chosen medium is rolled paper, in massive quantities.

Although she sometimes works with loose rolls of brown Kraft paper—as in her recent installation at the Phillips Collection—Ko more typically uses adding-machine tape, which she painstakingly removes from the small spools it comes on and rerolls into tight, heavy coils, using a modified potter's wheel.

Ko then wrestles and wrenches the coils out of shape, twisting and pulling them into strange forms (in the case of her latest work, spirals). Once the sculpture looks right, she holds it in place with strong clamps, applying a mixture of wood glue and pigment that fixes it permanently. (Ko uses Japanese sumi ink for the black pigment, calligraphy ink for the red.) The dried pieces are then sanded to a matte, woodlike finish.

The intensive process is a kind of strenuous, back-and-forth dance—between where Ko wants the paper to go and where it, by virtue of its own energy, wants to stay.

Washington City Paper,

City Lights: Saturday

March 9 - 15, 2012

"Jae Ko at Marsha Mateyka Gallery"

by Kriston Capps

For her exhibition at Marsha Mateyka Gallery, Jae Ko doesn't deviate much from her formula. That's not a bad thing. The sculptor, one of the Washington area's most consistent, has tapped an active vein with her rolled-paper sculptures, which she treats with glue and sumi ink. The works stand on the knife's edge between sculpture and drawing, and with every return to this format, she pushes them in one direction or another. These latest works fall decidedly along the drawing end of the spectrum. In black sumi and red calligraphy ink, these paper sculptures are elongated versions of works she has done in the past, like unwound springs; the twisting forms represent nothing so much as some sort of calligraphic script. And they look like the result of painstaking work, much as many drawings do. But the works are grounded in sculpture, too, with symmetries and rhythm that resist perfect regularity, just as in nature.