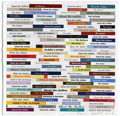

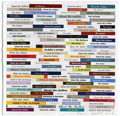

Dust jacket collage/poems featured on VISPO,

the Visual Poetry supplements of Coldfront magazine.

(Saturday, June 4th, 2016)

|

Marsha Mateyka Gallery

email: mmateyka@aol.com

2012 R Street NW · Washington DC 20009 · TEL 202-328-0088 · FAX 202-332-0520 |

|

Images Biography Artists Represented Gallery Home |

Buzz Spector |

|

Dust jacket collage/poems featured on VISPO, the Visual Poetry supplements of Coldfront magazine. (Saturday, June 4th, 2016) |

|

|

Reviews The Washington Post, Thursday, October 26, 2000, C5 "Galleries" by Ferdinand Protzman 'The Artist and His Books' : Eloquent Fictions at Mateyka "One of the ironies of contemporary art is that many conceptual artists require reams of words to explain their creations. Their theory-laden diatribes are usually an attempt to compensate for the artwork's vacuous visual presence. Simply put, looking at conceptual art is often so excruciatingly boring that the idea being explored is moot. Words can't change that. Many artists claim this visual void is necessary to focus attention on their ideas, an approach rooted in the 1960's, when conceptualism became a hot ticket on the international art scene. Back then, conformity was out and confrontation was in. In our Internet-driven, money-obsessed era, conformity dominates, and conceptual art generally seems more pretentious and pedantic that challenging. Torrents of images, ideas and words pour on us every day. Attention spans seem to grow shorter as telecommunication gets faster. Artworks that don't welcome our eyes never meet our minds. What keeps conceptual art going as a genre in this context aren't the doctrinaire old-timers like Joseph Kosuth, but a younger generation of hybrid artists such as Buzz Spector, whose work is visually compelling and intellectually stimulating. The photographs and mixed-medai pieces in Spector's exhibition "The Artist and His Books", at Marsha Mateyka Gallery, are overtly beautiful, a designation that would have gotten the artist from Champaign, Ill., drummed out of the conceptual ranks 20 years ago. Literature, books and bookmaking have been Spector's recurrent themes for 20 years, and these recent works, particularly the striking series of large-format Polaroid photographs, are fascinating distillations of his art and ideas. "My Fiction" is a self-portrait consisting of six framed Polaroid photographs, each about two feet wide and 31 inches high. The technology produces glossy images that are unusually deep for photographs and rich, saturated colors give the images a painterly look. The Polaroid process also leaves a border around the edges of the photo and a fringe of chemical streaks at the top, making these instant pictures seem slightly unraveled, like 17-century Flemish tapestries. Spector used that technology well. The piece shows him a balding, bare-chested, middle-aged man sitting amid stacks of novels from his personal library. Visually, "My Fiction" is a lush, colorful symphony of geometry, typography and figuration. The stacks of rectangular books, each with its own combination of colors and typefaces, form a semicircle around Spector. He leans forward on his novels, resting his cheek on one hand, in a pose that parodies both the standard book-jacket photo of an author and Botticelli's cherubs. Those references are a whimsical invitation to ponder fiction and what the notion of something invented by the imagination means to artists and writers. Thinking about all the invention and imagination that produced the novels Spector has read, by brilliant writers such as Dostoevsky, Kafka, Borges, Joyce and Bellow, is overwhelming. Spector apparently reads no escapist fiction. There isn't any Elmore Leonard or Robert Parker in the piles, just serious literary figures. But stack their works up like cordwood and the styles, plots and characters unique and powerful withing the context of a single book form a cacophonous, undifferentiated whole. The Brothers Karamazov and Leopold Bloom vie for attention, each calling us into his own, fictional universe. An idea lurks behind all those words and Spector's cherubic countenance" All art is fiction. Even photographs are just visual documentation of an invented moment, snapshots of a fleeting instant when an artist, viewing the world through the inescapable lens of subjectivity, saw something, felt something and took a picture. The result of that effort is another story, written partly by the artist's vision and partly by the person who looks at the image from his own subjective shell. The essence of being an artist means inventing and reinventing oneself and one's work by examining some of the basic dichotomies of human life, notions of reality and imagination, self and other, heart and mind, individual and collective. Such dichotomies also apply to artists' careers. They pursue individuation, differentiating their work from that of theirs peers. At the same time, they are scrambling to secure a choice spot in art history's collective pecking order, competing with the present as well as the past and the future. Cynical artists belittle the past even as they borrow from it, exploit the present and sell the future short to boost their standing on today's bestseller lists. Spector is successful. His work is in some of this country's top museums. But he seems sincere rather than cynical. Look at "(All the Books in my Library) by or About Ann Hamilton". Hamilton, who lives in Columbus, Ohio is another hybrid conceptualist and her work sometimes uses bits of text and the psychological and sensory aspects of books to examine issues of female identity. In a single Polaroid, Spector captures the essence of Hamilton's art. His picture, showing a V-shaped row of books, standing upright, pages facing out, is incredibly delicate and feminine powerful. It's more ode than idea, a song praising a woman, words, art, love, sex and life. Looking away is hard. That's the idea."

The Washington Post, Thursday, March 19, 1998, D7 "Galleries" by Ferdinand Protzman Buzz Spector at Mateyka Gallery: "Buzz Spector's bibliomania has been the driving force in his conceptual art since the early 1980's, and his obsession with books continues to produce some strikingly original work. "Authors", an exhibition of his new work at Marsha Mateyka Gallery, features collages made from book jacket photos of authors, as well as the artist's portraits of authors made from torn pages bearing a photographic image of the writer. The most engaging works in the show are the portraits. Spector takes their carefully posed book jacket photo and prints it on a number of pages, the meticulously tears each one and binds them together. The technique blurs the line between abstraction and figuration, giving the photographs a hard, conceptual edge. The results, displayed on lecterns, make the faces of writers such as Umberto Eco, John le Carre and Betty Smith seem to emerge from the tattered pages of a wellworn book as if they were asking what their appearance has to do with their prose. Spector also pokes fun at the trite book jacket poses in his titles, which include Authors ( hand on Beard ) and Authors ( Finger to Temple )."

Articulate, issue 28, April, 1998 page 8, review by Kurt Godwin "Nationally recognized conceptual artist Buzz Spector's current exhibit concerning the world of literature is well suited by the dark wood paneled, old world library/den atmosphere of the Marsha Mateyka Gallery... ...In the front of the gallery, podium like structures protrude from the walls displaying facsimiles of open books with manipulated photographs of various authors rather than text. These images have been meticulously torn into thin horizontal strips, then reconstructed utilizing the ragged white ripped edge as a wavering pattern. The effect is reminiscent of flickering static from an impaired black and white television. The clarity of each subject ebbs and flows as distinguishing features shift between recognition and obscurity. The austere podiums act not only as book stands, but also as commemorative trophy pedestals to authors whose identities remain "literally" elusive. Similarly, when one becomes engrossed in a book's development, the identity of the author fades into the background, leaving in place the world the writer has created. Can this literary world be a surrogate for the author's identity? Or has the author hidden his true nature behind the facade of his tale? Questions lead to questions in this cerebral house of mirrors."

On Paper, Vol. 2, no. 6, July-August, 1998, p. 47. review by Jori Finkel "...Spector has recently shifted from books to authors, exploring the ways in which they are similarly packaged - i. e., in the form of publicity stills and marketing materials... the torn-book portraits filled the gallery's front room. His procedure involved ripping one page after another so that, from the composite

layers of paper, a portrait emerged. Scarred by jagged horizontal lines, these

portraits are mesmerizing in their own right...Spector has long been obsessed

with the physical manifestation of intellectual activities, the weight of

thought, and the machinery of reading and writing." Art Papers, Nov/Dec 1998 Buzz Spector: Authors Marsha Mateyka Gallery, Washington March 6 -28 By Dinah Ryan From his position as a theoretician’s artist, Buzz Spector has won both praise and criticism for exploring and toying with overarching concepts: the idea of the book, the text, the art work, or the artist/author. In “Authors” something slightly different occurs. In this case the source material--publicity shots and dust jacket photos of authors--originates from a commercial source: the marketing and public relations departments of publishing houses. One of the peculiar aspects of a writer’s career is the commodification of the book (which has to sell, after all) and the subsequent construction of a writer’s image as an established part of the process. In a very concrete sense, then, Spector begins here with material which has already been emptied of identity and preloaded with persona. Spector’s work was assembled by two methods. In the first group, large-format portrait photographs of unnamed individual authors were printed in multiples and stacked and bound into books resting on wall-hung lecterns. The pages of each book were torn in progressively narrowing strips so that the author’s portrait was “read” through a series of frayed, horizontal disruptions, as if it were received via the poor reception on an old black and white television set. In “Authors (Man with Pencil)”, a writer sits with a pencil pressed against his upper lip; in “Authors (Finger on Temple)”, a woman of thoughtful, gently-faded prettiness rests her finger against her temple. Such “authorial” poses are commonplace and ready-made, yet as seductive, in their way, as the tilted chins and pouting lips in fashion photographs.

In a passage from his 1993 essay “The Position of the Author”, which was offered as his

artist’s statement at the Mateyka exhibition, Spector wrote: “closing the book we stare

in disbelief at the image of the person whose words have excited us so. Is this not part

of what Barthes meant by the death of the author ?” Possibly. Something wistful, naive, and

understandably frustrated in Spector’s statement underscores what happens in front of the

sedimentary layers of his “Authors”. The viewer continues to search, though somewhat

pathetically, for something distinct, for a “sign that is not a sigh”, a glimmer of the

elastic capacity of ideas to agitate and animate us. The difficulty is that these images

probably never contained the germ of authenticity in the first place. Spector’s books

are, therefore, bleakly and ironically funny but they also leave behind a kind of

beautiful sadness, a nostalgia which is the inevitable result of pointing out the

emptiness of materials which are congenitally vacant. The Washington Post, March 2, 1996, pC2 Galleries: "Conceptual Art and the thought behind it, It's the Thought that Counts" By Ferdinand Protzman It's the idea, stupid. While conceptual art has no official motto, that fills the bill for a phenomenon in which the idea of a work is more important that the finished product. There may not even be a finished product. Or if there is, it may be made visually uninteresting as a way of focusing attention on the artist's idea. Conceptual artists aim not to delight the eye but to raise questions about the nature of art, to expand its boundaries, to provoke discussion, to make us think. That seems admirable. Unfortunately, the results are often pretentious, hollow and just plain boring. There is a lot of truly awful conceptual art out there, probably because there is no dearth of bad ideas. Fortunately, there are also some good ideas and some conceptual art that is capable of stimulating the viewer aesthetically as well as intellectually. Two examples of the art form at its best can be seen in the Dupont Circle neighborhood at Marsha Mateyka Gallery, which is showing "Painting by Buzz Spector, and at Troyer Fitzpatrick Lassman, in "Gillian Brown and Inga Frick: Recent Works". Spector is an internationally known conceptual artist who teaches at the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana. His works are in New York's Museum of Modern Art, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Corcoran Gallery. Over the past few years, his work has focused on books and his personal library, and is meant to stir discussion for the way books collect ideas and connect us to one another and to the past. There are a lot of books and not one painting in his exhibition here. The works on the walls look like smallish abstract paintings, but are actually books in which each page bears the same image. Pieces of each page have been carefully torn out in incremental lengths, the first almost to the binding, the last left intact, creating feather layers of ephemeral imagery. The works are mounted in enameled aluminum frames and sell for $3,500 each. Some of the works are monochrome fields of white or gray, printed with text, such as "the red room", or "conceptual art". Others are subtly colorful abstractions, reminiscent of Jackson Pollack. All of Spector's "paintings" have remarkable texture and great depth that comes partly from knowing that the text is literally layered, appearing in the same place on every page, from first to last. There also is a lot of space for the imagination. The piece titled "The Red Room" bears these words, but not a trace of the color or of a room. Yet it is almost impossible not to see a red room in the mind's eye when looking at it.

The artist used to work with old books, treating them as found objects and tearing

or altering them into different forms. But the destructive element bothered him,

so he now creates the books he tears. The gallery, which represents Spector in this

area, is also showing several altered books and collages made of altered

postcards. Those works sell for between $1,100 and $4,000 |