|

Art in America

December, 2002, p.114

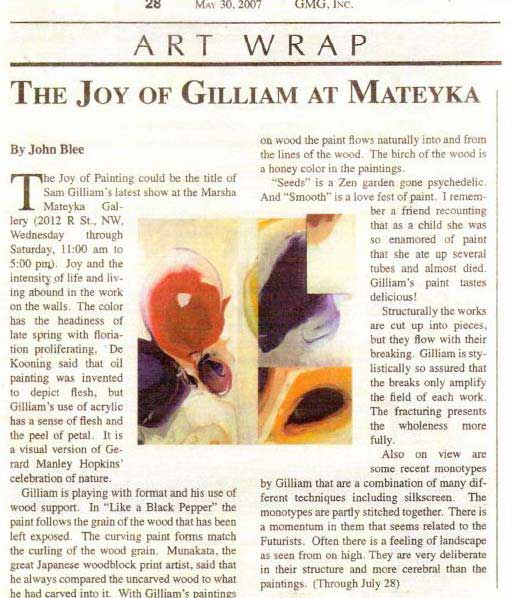

"Washington, D.C., Sam Gilliam at Marsha Mateyka"

by Joe Shannon

Sam Gilliam's new work, a series called "Slats", is a major departure for him. When one thinks of Gilliam's art, scale and emotional power come mind. Gilliam's protean career has covered a lot of ground, from the colored canvases draped unforgettably over and around the Corcoran Gallery's atrium to large fields of explosive and emotive color on stretched canvases. Then there are the wonderful monumental constructions made of shaped birch plywood, variously joined and hinged and painted, that rank there with the drapes as his greatest achievements.

All of the paintings in this recent show are, by past standards, small and cool- restrained in scale and austere in effect. "Blue Slat" ( 2002 ) is only 30 b 24 inches. It consists of five slats, all painted a rich blue that varies only minimally in each section.

The paint is thickly poured on the plywood, then polished down to 1/16 of an inch. In each work there are usually four or five sections of different sizes, joined together but not necessarily flush. The height of the slats usually differs by a fraction of an inch. "Small Yellow Slat" ( 2002 ) is only 16 x 13 inches, but it has a precious, luminescent vibrancy. Built around an inverted "L" mounted over a smaller square at lower left, with a narrow horizontal rectangle added at the top, there's not much to it, right? Wrong. Mysteriously, this beauty speaks eloquently of esthetic subtleties of many kinds.

Most of the works are monochromatic and simply constructed, but the variations are endless. The edges are important in all the works; variations on the rectangular matrix of the pieces are as emphatic and improvised as this simplified mode allows. In "Red Slat", on the perimeter of the right lower quadrant, a tall thin rectangle extends by about an inch; nearby, a wider rectangle falls approximately an inch below the matrix line. This simple, telling maneuver, along with the scale and composition of the slats, their glittering surfaces and the stare of the simple colors, make the experience of viewing these works anything but Minimalist.

The Washington Times, Saturday, April 13, 2002

ON VIEW: Slats, Paintings fit in color and form

by Joanna Shaw-Eagle ( excerpts )

Sam Gilliam points to "Blue", one of his nine new minimalist works at the Marsha Mateyka Gallery in the Dupont Circle area. It's part of his exhibit "New Paintings: Slats", which he considers his best to date.

For a half-century the artist, 69, has come up with intriguing, challenging and sometimes extraordinarily sensuous and beautiful artwork.

The "Slats" paintings are spare, rectilinear and decorated with single acrylic colors. Mr Gilliam joins smallish plywood rectangles vertically of horizontally to create larger asymmetric rectangles. He pours layers of acrylic paint on thin panels of birch plywood to give them a seductive high-tech industrial polish. The artist then suspends the rectilinear images from the wall.

The works are radically different from the complexly organized and boldly colored earlier paintings that often verged on sculpture. Standing near "Blue Slat", one of the medium-sized works in the show, Mr Gilliam says, "It's just in the cards that you'll do something different next." He notes he had wanted to make this kind of reductive art since the 1960's.

The artist says he first saws plywood to make the cutouts, then combines them for the larger shapes. " A big challenge is making the form, and the hardest thing is finding the surprise in each shape. The interesting thing is that they're so hard to do," Mr Gillian says.

The slightly stooped, 6-foot-plus artist with salt-and-pepper hair says he believes art should not be talked about. With a sheepish smile, he looks for a variety of topics, " the Palestinian-Israel conflict, the place of color painter Howard Mehring in the history of Washington art " to avoid discussing his work.

Mr. Gilliam points to where he joined sections in "Blue Slat." His gentle hands, with their gracefully attenuated fingers and nails, touch one of the joints of the work. He explains how he wanted the joint to become part of the surface "like a painted seam".

Each painting has its own attitude that comes from the paint. "I pour the paint unevenly with different colors for slightly serrated surfaces. Some of the paintings even have small bumps. When I get near the top surface, I decide what the final color will be," Mr. Gilliam says.

Viewers will see this in "Large Red Slat", in which touches of blue vibrate through the richness of the red. The multiple pourings of acrylics also make for highly shiny surfaces, which the artist says he hasn't attempted before.

Although the works look strictly rectilinear and geometric, Mr. Gilliam still uses the stream-of-consciousness techniques of his famous "draped paintings" of the 1960's. Improvisational in nature, they were large color-saturated, unstretched canvases that he gathered and hung like curtains from walls and ceilings.

In "Blue Slat", he points out the flat upper section, which is colored with a light, but intense, blue. It thrusts into the painting's main midsection, which deepens into a darker, almost inky blue. The artist says he intentionally meant the artwork to be smaller than a painting called "Big Blue Slat" and have lots of space around it.

Mr. Gilliam crosses the gallery that was once an elegant, late 1880's home to talk about "Big Blue Slat". He gave this painting more physicality and more complicated working of color, he says.

The artist considered how all the paintings would look together in the gallery, and this is where his mastery of color and form is most evident. Mr. Gilliam placed the large blue painting next to a corner that held a smaller yellow one so the colors would bounce off each other. He also painted a series of smaller works for the gallery's hallways and middle room.

The artist says the early modernist Dutch designer Gerrit Rietveld inspired his latest works. Mr. Gilliam first read about the constructivist furniture designer's work while he was in college. The artist especially admires Rietveld's reduction of chairs to rectilinear wood planes, often slats, painted in primary colors. Hence the name of Mr. Gilliam's show.

For the first time in his long career, Mr. Gilliam has designed sets for a Washington Ballet production. "Journey Home", with a Sweet Honey in the Rock musical score, was performed last week at the Kennedy Center and now goes on tour. "The sets weren't sets, they were like moments in the dance and play. We were trying to give an armature, to give it eight images," he says.

He made 20 elements for the "blue set", that the dancers could rock back and forth. In another, he created a red piece that dangled from the ceiling like an umbilical cord with a draped painting above it.

"Never before and never again", he says of the experience. "The results of the collaboration were the best thing for the Washington arts community, but it's difficult for me to go without doing my own work".

Mr. Gilliam has done public commissions for places, from Helsinki, Finland to Seoul to Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport. He has received honorary doctorates of arts and letters, and his work has been shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Tate in London among other art institutions.

Washington City Paper, April 19, 2002

ARTIFACTS

"Less is More"

by Garance Franke-Ruta

Walk into the Marsha Mateyka Gallery on R St., NW and you'll be greeted by a series of smoothly minimalist rectangles, each in a single hue of blue, green, red, or yellow. The works, plywood panels, with their shiny, subtly metallic pigments overlain with thick layers of acrylic medium, are themselves assembled from smaller rectangles that have been fitted together likeelements of a puzzle. The effect of the pieces is arresting and a decided departure for Sam Gilliam, one of D.C.'s best-known artists.

Gilliam, 68, long worked with jagged, swooping lines and a multiplicity of colors in his paintings and painted sculptural installations. His work was raw and fluid, with colors bleeding into one another and thick overlays of conflicting and complimentary patterns. Critic Walter Hopps once remarked on the "delicate balance between improvisation and structure and a sense of chaos controlled in Gilliam's works". The artist's new exhibition, on view at Mateyka to May 18, shows no evidence of chaos at all. "It was time for a change", Gilliam says.

"After moving into a new house and painting stripes on the wall, I was ready", he explains of his foray into simple planes of color. "The prints came first." Working on a computer, Gilliam in

2001 designed a series of templates for pieces such as that year's "Union Pacific" and the series of diptychs and triptychs that followed. Working with Tandem Press in Madison, Wis., he

collaged birch veneers onto paper and printed them with simple ovals and pure geometric shapes. "Before. I would always overprint, overstain", says Gilliam, "This time [ I chose ] just to

print a single time". The paintings followed from this newly restrained approach.

Though Gilliam had previously worked with acrylic on plywood, in the late 1990's, he had moved his riotously colored pictures into three dimensions with a series of hinged parts that defied painting's traditional flatness. Now, inspired by modernist Dutch designer and architect Gerrit Rietveld, "who was influenced by painter Piet Mondrian and made furniture reduced

to planes of wood painted in primary colors" Gilliam returned to the flatness that he so long avoided. And he's christened his new works "Slats", in homage to the shapes from which someof Rietveld's chairs were built.

"Unless you have this kind of freedom in the materials or the way you make art," Gilliam says, "by some standards, you may not be an artist."

"National Reviews: Sam Gilliam at Marsha Mateyka,

Washington, DC"

by Rex Weil, ARTnews, February 2000, p. 168

Washington patriarch Sam Gilliam continued his exploration of the conceptual space between painting and sculpture in this inaugural exhibition with his new dealer, Marsha Mateyka.

Since his 1960's post-Washington Color School stained canvases, Gilliam generally has been content to sacrifice traditional painterly illusions for a formidable her-and-now material presence. His major works, many commissioned for public spaces, are huge, complex wood, metal and canvas constructions. They function both as paintings and as architectural elements in the buildings they inhabit.

The new works here pushed the formal ambiguity further still, by incorporating images and movement. The central panel of "Summer", a triptych and one of the highlights of the show, is a tall, narrow slice of birch plywood hung flat against the wall. Gilliam has attached half-width wood panels to both vertical sides with long piano-lid hinges. Thus, like an altarpiece, the work may be opened, closed, or--as exhibited here--left partially ajar, with the "doors" jutting into the gallery. Both sides of each panel are brightly colored, so even the tiniest shift in position causes a permutation in the overall composition. ( Though viewers were not supposed to move the panels on their own, they were encouraged to request gallery assistance in order to view the changes.)

In constructing these panels, Gilliam laminates thin, transparent layers of synthetic pigment to the work, creating a perfectly smooth surface--a significant departure from the artist's signature "raked " crusts of thick acrylic paint. When "Summer's" panels are open, we see black skeins flowing through violent red, cerulean blue , and sunny yellow. A ghostly photographic image of a flower is visible under the paint near the top of the work. "Summer" "closed" is a strange, icy, metallic blue.

In "Along the Canal", the artist moves even closer to a full-blown image of nature. Though this work does not incorporate movable panels, it is painted on a series of rigid horizontal steps attached to the wall. Nonetheless, it gives the impression of flexibility, as if it could be collapsed and expanded like the folds of an accordion bellows. Its glossy pink-oranges and deep blues suggest a dawn horizon over an agitated sea.

Review in The Washington Post, Thursday, November 4, 1999

by Ferdinand Protzman

"Pushing the Drapes Aside, Sam Gilliam's Old Works are a Window on the New"

Sam Gilliam's first taste of success came in the late 1960s with his drape paintings,

which brought the Washington Color School's raw, stained abstract canvases literally out

of their frames and off the wall. Back then, they were colorful, innovative, spectacular

and very now.

In our now, they're beautiful, still-spectacular specters that seem to haunt every

Gilliam exhibition. Attend the opening of one his shows and you'll encounter someone,

usually a person who was young, hip and high in 1969, saying his latest work is nice,

but the drape paintings, they were really great, you know?

I don't. The implication is that Gilliam, Washington's best-known artist, a man

whose works are in major museums across the United States and Europe, peaked with the

drapes and his subsequent work hasn't quite measured up.

People can provide several arguments supporting that conclusion. His collages and

constructions, like those currently on display at Marsha Mateyka Gallery, strike some

as unfocused, diffuse and packed with too many diverse elements: references to European,

American, African and Asian art, rubbery materials, piano hinges, push pins, plywood.

The inspiration seems borrowed synthesized. Not like the drape paintings. They were

original.

It is a puzzling attitude and its wrong. Which isn't to belittle the drape paintings.

When I was a student at Oberlin College in 1973, the Allen Memorial Art Museum acquired a

Gilliam painting that was draped over a sawhorse. It's a beautiful artwork, colorful, soft

and lyrical but with tensile strength, a simple idea with complex visual and intellectual

overtones, the kind of work that resonates for a long time.

The same thing can be said of Gilliam's new work at Mateyka. But the resonance is different.

To use a musical metaphor, the chord structures, key changes and rhythms are more complex, in

some cases bordering on chaos. There's an awful lot going on in some of these pieces, particularly

the collages. But the music is coming from the same place that produced the drapes. A clear,

logical line connects the old work to the new.

Gilliam has pursued the notion of making three-dimensional paintings since early in his career.

That's why he created the drape paintings and brought the picture into the viewer's space. Before

he abandoned the frame and the wall, he was a gifted and thoughtful colorist, like Morris Louis,

Kenneth Noland, Gene Davis and the other Washington Color School artists.

It was inevitable that his quest for 3-D would lead him toward sculpture and that the presence

of the object would occasionally obscure some of its painterly qualities. But the changes are not

that great. The birch plywood and piano hinges of a piece like "Summer" in which Gilliam succeeds

in painting every hue of a Washington summer day on few panels, create a flexible surface that

extends into the room. Think of the wood as canvas and the hinge as both a grommet and a fold in

the fabric. Sound familiar?

Despite their physical limitations, some of the plywood pieces are metaphorically richer than

some drape paintings. "Along the Canal", for example, is a modest-size piece, about 3 feet high

and 2 feet wide, made from four birch plywood panels painted with acrylic. The top panel is shaped

like a half-moon. Beneath it is a rectangular panel, with two smaller panels attached to its sides,

forming wings. When closed, they obscure the underlying panel.

The lovely mix of colors-scarlet, lemon, magenta, brown and blue, to name a few-suggests an

autumn day on the banks of the C&O Canal. When the side panels are open, the work seems like a

medieval altarpiece devoted to Washington's natural glories. Close them and it's a pure abstraction,

geometric shapes and fields of barely modulated color. That's a quick trip through a art history

in a small package.

Some of Gilliam's plywood paintings in the past few years haven't had as much condensed power

as his new works. But not all of the drapes were kickers, either. Few artists produce an unbroken

string of masterpieces.

His collages, made from pieces of paintings stuck together with push pins, have also been uneven

at times. Some seemed overly whimsical, others forced. At times, it seemed he was going in an unpromising

direction.

That isn't the case with the new collages. They are like cubist African kimono sculptures. They

have the flow and formal presence of the Japanese garment, the fractured planes of a Braque painting, the

vivid colors of West African art and structural and compositional elements drawn from European, American

and West African sculpture. All that in three dimensions, encased in a glass box.

Is it a synthesis? Absolutely. That's what makes Gilliam a great artist. He's a master synthesizer,

following his own path but constantly absorbing influences and turning them into something fresh, unique

and compelling. Unlike some artists who've had relatively early success, he's had the courage to keep

exploring. And he didn't let the drape paintings become a product or trap.

"I realized how much they meant and I realized I had to lose them," Gilliam says. "The drape painting

was only thinking. The roots of that thinking are in what I do now. Your have to ask yourself what kind

of artist you want to be. I had to get out on a limb and then decide how I wanted to get back. You have

to constantly challenge yourself to find inspiration and to learn how to work. That's the most important thing".

SAM GILLIAM, "Works '99"

October 15 - November 27,1999 PRESS RELEASE

It is with great pleasure that the Marsha Mateyka Gallery presents

its first solo exhibition of the work of the renowned artist, Sam Gilliam. This

exhibition will focus on his paintings and collages of the last year. It will be on

view through November 27.

Sam Gilliam's work first gained national prominence in the late

1960's with the debut of his dramatically innovative drape paintings. Since that

time, he has had a long illustrious career, which has included numerous

awards, grants and important public commissions. His paintings are in major

museum collections including the Metropolitan, MOMA and the Whitney, in New

York; Art Institute of Chicago, Menil Collection, Tate Gallery, London, Musee

d'Arte Moderne,Paris, and all the major museums in Washington, DC.

Sam Gilliam's most recent museum exhibition was at the Kreeger

Museum in Washington. The following excerpts are from the exhibition

catalogue:

"Gilliam's recent work continues to express his fascination with

structured improvisation. He is now creating vividly colored three-dimensional

constructions of acrylic on birch plywood, often with collage elements.

...These new paintings are as complex technically as they are

spatially. Gilliam begins by staining sheets of plywood with acrylic and polymer

paints, sometimes in a gel medium that creates a translucent, almost glassy

surface. The sheets are then cut up and cut out... The parts are then hinged

back together on either side of a stable center, creating wings in the manner of

medieval altarpieces.

...Gilliam has always worked in series; his current paintings are no

exception...Working in series allows him to explore chromatic and compositional

relationships not only within a painting, but between several paintings in a suite.

...Collage has likewise been a consistent feature of Gilliam's work

over the years. Typically the artist has pieced together the cut-ups of his own

paintings.

...Like Matisse's cut-outs, Gilliam's paintings aspire at once to

chromatic and compositional intricacy and to material and technical invention.

Playful but serious, they embody a commitment to modernism...They are a

celebration of artistic freedom, of the power and the primacy of the individual

imagination: this is one of the fundamental articles of modernist faith".**

**"Gilliam in 3-D", catalogue essay by John Beardsley, The Kreeger Museum,

Oct 16, 1998 - Jan. 2, 1999.

|

and he's still finding ways to tweak that traditional format. The four 2009-10 "Tempo"

paintings, which are acrylic on nylon, are joined here by three new works on canvas, whose

colors are less bright and textures more subtle. Where the pigment seems to flow on the

nylon, retaining a sense of fluidity, it seeps into the canvas, melding color and form.

The earlier paintings are stitched together, so that only the drape can change in different

installations; "Tinkerbell's Bookcase" (composed of four pieces) and the knotty "Gordonian"

can be arranged and rearranged, theoretically, in infinite variety.

and he's still finding ways to tweak that traditional format. The four 2009-10 "Tempo"

paintings, which are acrylic on nylon, are joined here by three new works on canvas, whose

colors are less bright and textures more subtle. Where the pigment seems to flow on the

nylon, retaining a sense of fluidity, it seeps into the canvas, melding color and form.

The earlier paintings are stitched together, so that only the drape can change in different

installations; "Tinkerbell's Bookcase" (composed of four pieces) and the knotty "Gordonian"

can be arranged and rearranged, theoretically, in infinite variety.